New in

![]()

![]()

New arrivals

Ready-to-Wear

![]()

![]()

Ready-to-Wear

Each item is thoughtfully selected to complement your wardrobe with timeless sophistication.

Ready-to-Wear

Each item is thoughtfully selected to complement your wardrobe with timeless sophistication.

Made-to-Measure

![]()

![]()

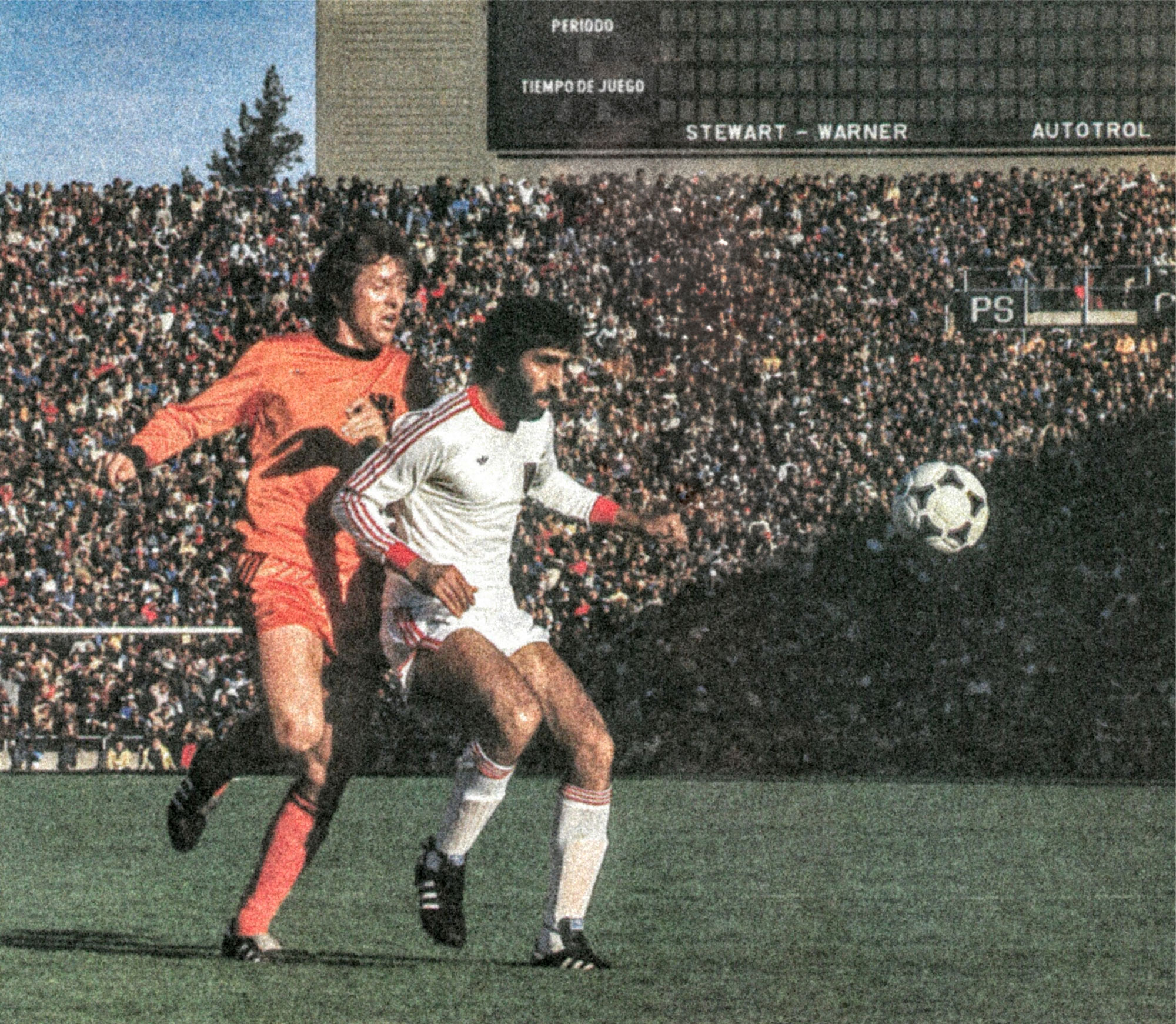

Spring/summer looks

- Refined luxury meets the relaxed freedom of spring and summer with effortless tailoring.

- Discover looks

Clothing

Accessories

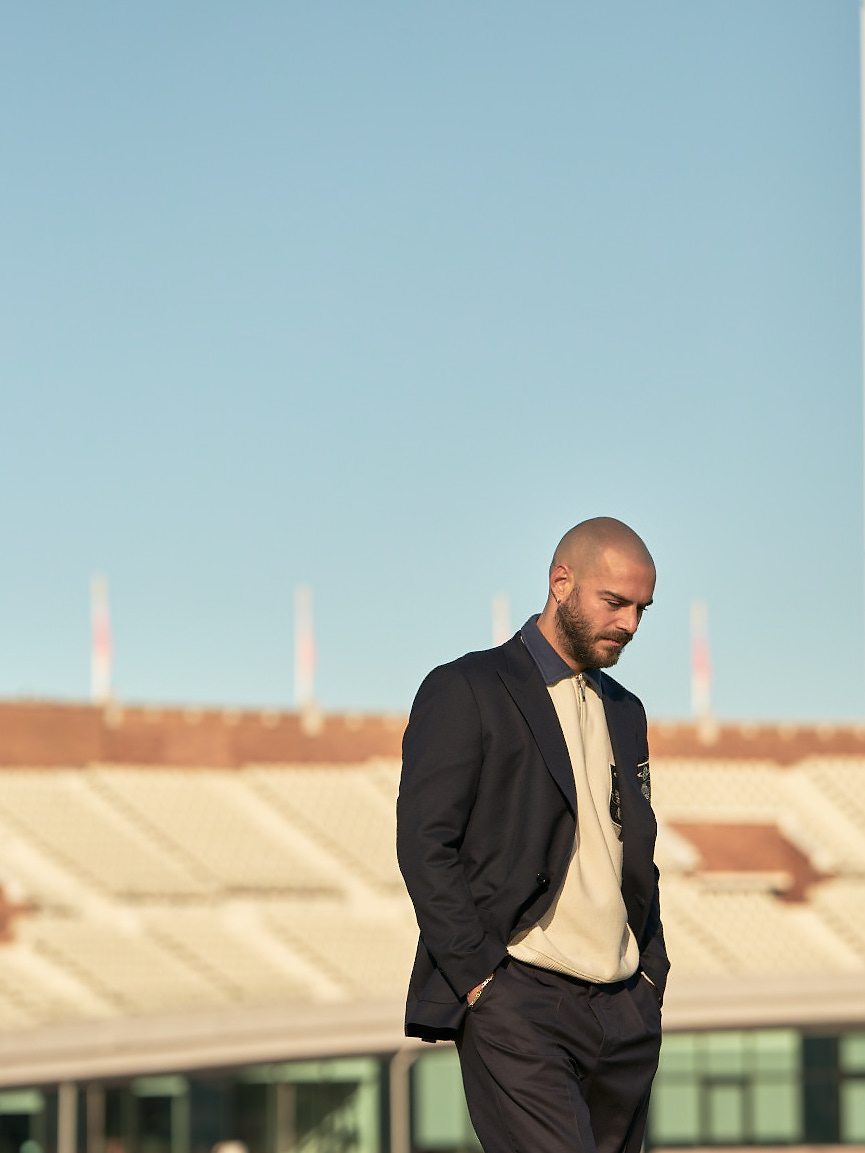

Made-to-Measure

Tailored to your body and style, designed down to the smallest detail.

Made-to-Measure

Tailored to your body and style, designed down to the smallest detail.

Wedding

![]()

![]()

Get wedding ready

- Whatever you have planned, we can help.

- Discover more

Wedding looks

- Wether you’re the groom or a guest, explore some of our favourite looks to discover the one for you

- Discover more

Our story

![]()

![]()

Our community

- A snapshot of some of the great people creating key pieces with us

- Discover more

Becoming a client

- Once you’re in, you’re in. You’ll be able to explore all the possibilities and experience unparalleled personal service.

- Discover more