New in

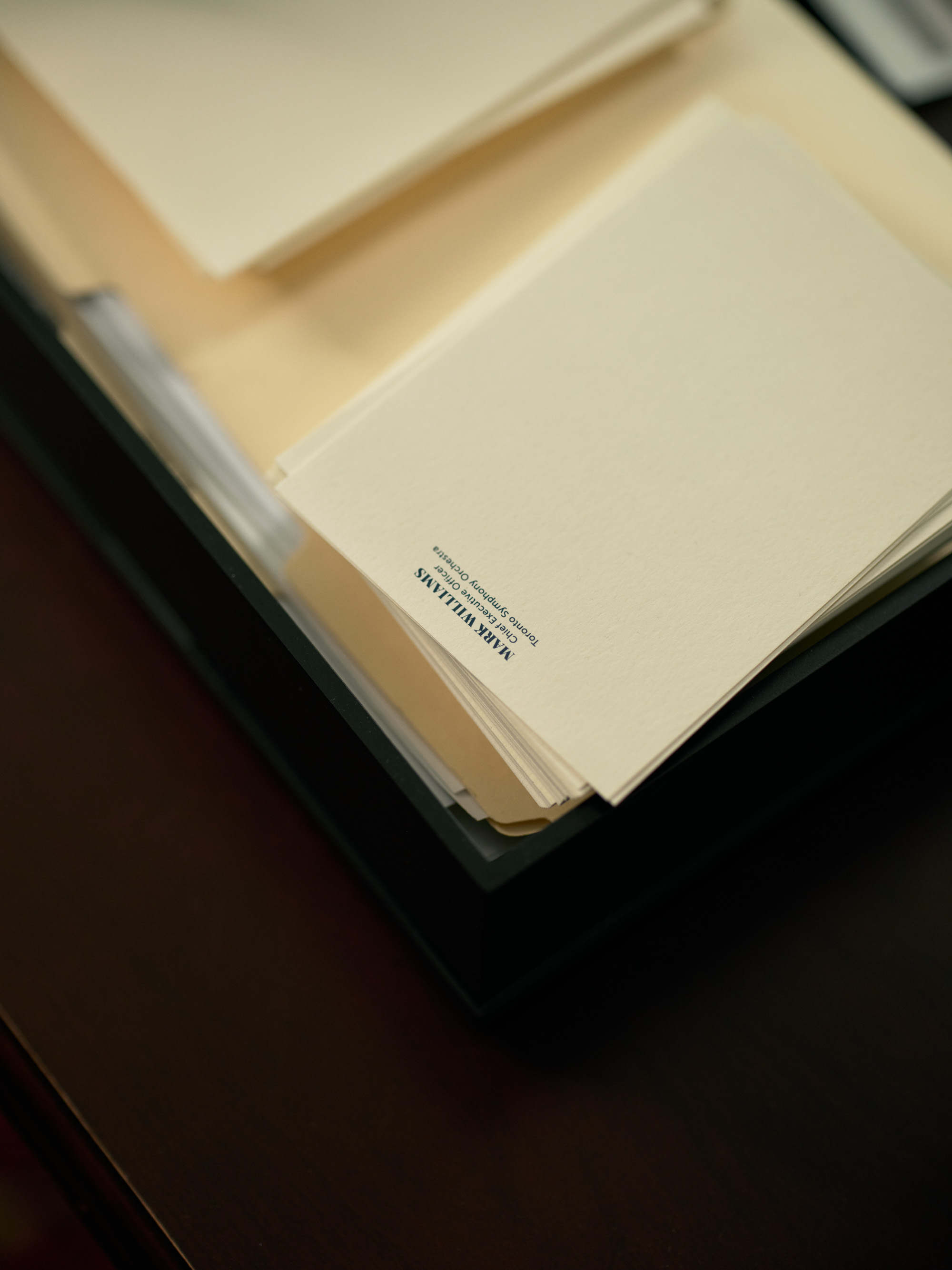

![]()

Spring & Summer Tailroing

Modern refinement inspired by Southern Italian heritage. Designed for natural ease and enduring sophistication.

Ready-to-Wear

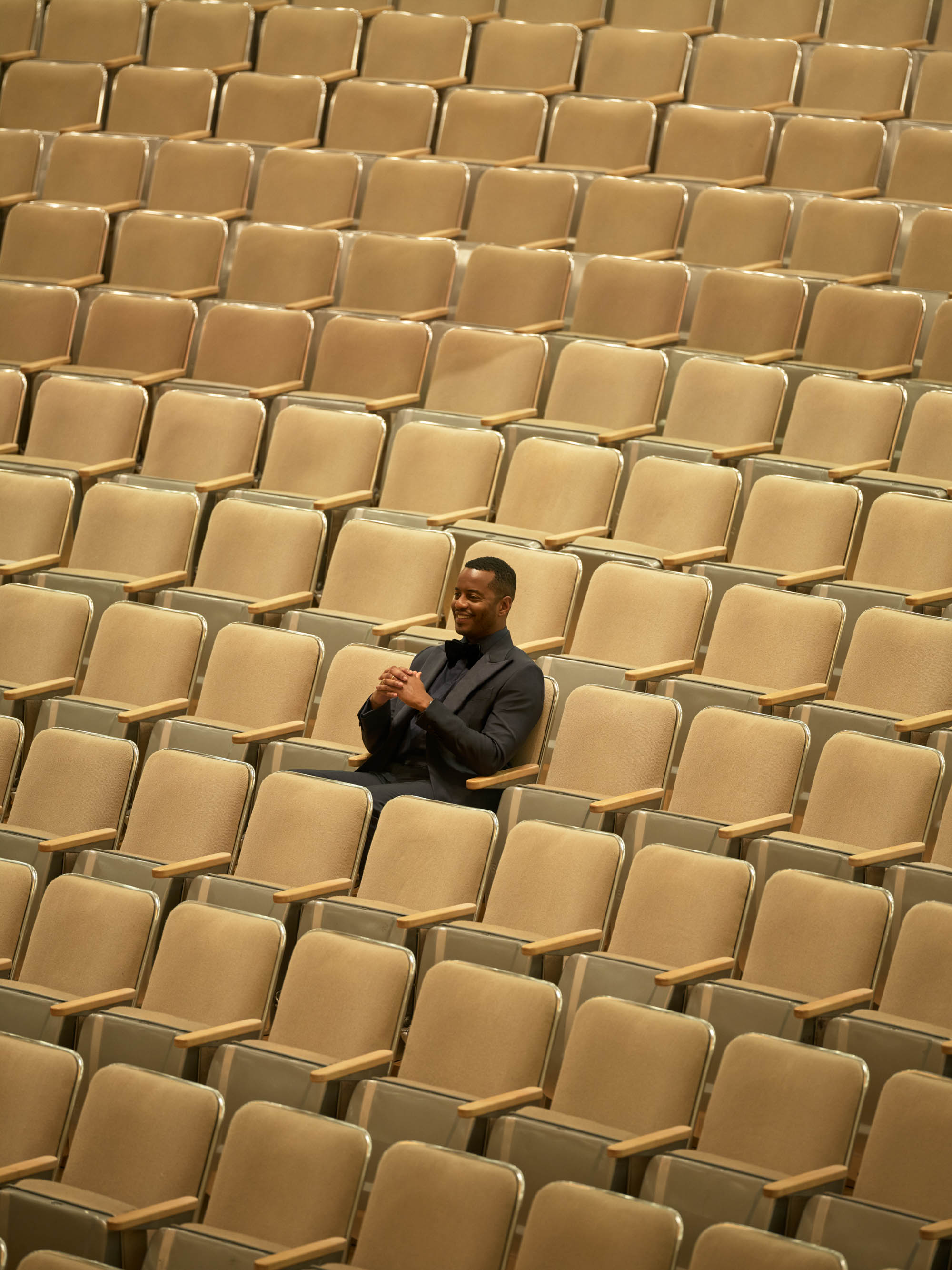

![]()

Seasonal looks

- Each item is thoughtfully selected to complement your wardrobe with timeless sophistication.

- Discover Spring & Summer Looks

Accessories

Ready-to-Wear

Each item is thoughtfully selected to complement your wardrobe with timeless sophistication.

Made-to-Measure

![]()

Spring & Summer looks

- Modern elegance, rooted in heritage craft. Designed for those who value tactile richness and timeless refinement.

- Discover looks

Accessories

Made-to-Measure

Tailored to your body and style, designed down to the smallest detail.

Wedding

![]()

Get wedding ready

- Whatever you have planned, we can help.

- Discover more

Wedding looks

- Whether you’re the groom or a guest, explore some of our favourite looks to discover the one for you

- Discover more

Our story

![]()

Our community

- A snapshot of some of the great people creating key pieces with us

- Discover more

Becoming a client

- Once you’re in, you’re in. You’ll be able to explore all the possibilities and experience unparalleled personal service.

- Discover more